Introduction

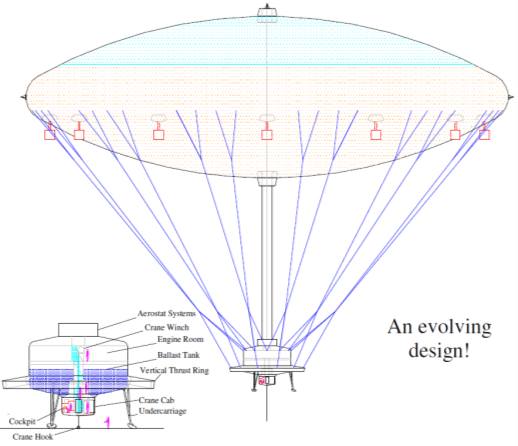

The following explanations were written to answer questions about heavy-lift omni-directional (OD) buoyant aircraft for this 21st Century, which is one of LBA’s longer-term objectives. The aircraft featured right typically shows our LS-L150 proposal for this. It’s an evolving design to transport 150 tonne underslung payloads (anything) with point-to-point precision practically anywhere, functioning as helicopters do but quietly with long range/endurance and outsized seriously-heavy payloads.

LBA also pursues unidirectional (UD) types, which some operators may prefer or need for the particular abilities they have. However, as for aeroplanes and helicopters, they suit different duties because of the different way they operate – needing airflow alignment, which our OD designs don’t need. This is important for fixed mooring, precise station-holding and orientation ability when operating in variable weather as aerial-cranes, difficult for UD types to fulfil

What are HTA and LTA?

What are HTA and LTA?

These acronyms are technical terms that just mean heavier-than-air and lighter-than-air. The terms are used to describe aircraft as well as their: parts, systems, materials and substances. Aircraft weight relative to the weight of external air it displaces is important with regard to the way air acts on them under the influence of gravity and wind. General aviation aircraft fall into three categories:

- Nonbuoyant types that don’t use an aerostat, so essentially are HTA aircraft unable to noticeably displace the atmosphere. They usually need propulsion for high airspeed over their fixed wings or motors to spin their rotor blades, needing associated high power to gain sufficient aerodynamic lift for flight. They take off and climb when aerodynamic lift is greater than their all-up-weight (AUW). Then later descend from reduced airspeed, losing some aerodynamic lift, and land with AUW transferred to the ground for support as airspeed, so aerodynamic lift, is lost.

- Near equilibrium (EQ) buoyant types with an aerostat are airborne before flight due to buoyancy lifting them. This ability stems from atmospheric displacement the aerostat causes before the aircraft’s release. When LTA (so buoyancy is a little greater than AUW) they thus can launch vertically by simply letting go of restraint lines, then flying using zero to low-airspeed aerodynamics/power. Later, when returning to the ground for capture while remaining afloat, they can use negative aerodynamic lift from airspeed over the aerostat as an aerodyne and/or vertical down thrust to descend. They also can release some LTA gas to reduce atmospheric displacement – reducing buoyancy to become HTA. Air as disposable ballast also can be taken onboard and compressed in tanks to increase density and thus AUW. Otherwise, when HTA, they can launch with a short impulse of vertical thrust to gain momentum and then fly as previously explained.

- Types between these classes use a smaller aerostat with reduced displacement size, so are semi-buoyant aircraft, needing greater aerodynamic lift for controlled flight. They are not hybrids, as HTA & LTA are not separate sciences, instead being related aeronautical aspects or conditions of flight. Also, they use all of the parts, systems and methods that near EQ types use, including a combination of both aero-dynamic and aero-static lift to fly with moderate power to maintain airspeed.

HTA thus relates to aeroplanes, rotorcraft, missiles, etc that don’t use an aerostat for buoyancy, which is a choice! In the near EQ buoyant aircraft class, there are tethered-aerostats, free-balloons (drifting with the wind) and dirigibles (i.e., airships), all buoyant-aircraft with an aerostat filled with LTA gas. This gas enables its form to function as a flotation aid for support of AUW (including the gas, which is the only truly LTA substance used). Semi-buoyant aircraft are new types yet to enter service and prove their worth. They use a smaller aerostat unable to support max AUW in the air but don’t need so much aerodynamic lift as HTA types to then fly. They also may fly a little faster but at greater cost from greater complexity.

What makes them float in the air?

Buoyant and semi-buoyant aircraft use an aerostat that enables floatation in accordance with Archimedes’ principle to displace the atmosphere (air), developing buoyancy (aerostatic lift) proportional to the weight of air displaced as a result. This is a natural effect due to gravity, but acts in the opposite direction, where light vessels are pushed up by the medium they are in.

Archimedes’ principle states “a body floating or submerged in a liquid is buoyed up by a force equal to the weight of the liquid displaced”. In this respect, the atmosphere (air), behaves in a similar way to liquids. Indeed, our own body experiences the buoying effect; where, if one weighed oneself in a vacuum chamber (not recommended), it would be found that our ‘true weight’ is a little more (by about 700 gm, generally not noticeable) than our ‘effective weight’ in the atmosphere. In water buoyancy is noticeable because water has somewhat greater density.

The science for buoyancy in the atmosphere is similar to buoyancy in water, where gravity acts on both of these fluid substances, drawing them towards the Earth – upon which they lie and get weight as a reaction result. The column of air lying against the surface thus has significant weight and therefore atmospheric pressure, which diminishes with column height. Vessels (or bodies) in the atmosphere displacing it therefore get an applied varying external pressure that is greater on their lower face than it is on their upper face trying to crush them but also with resulting upward force due to the pressure difference between lower and upper faces, tending to make them float against the vessel’s weight.

Such vessels in the atmosphere are called aerostats and do float when their AUW (including internal contents) equals or is less than the external buoying force pushing them up, provided they are not crushed by atmospheric pressure. This is the tricky bit, because lightweight large thin empty vessels (i.e., evacuated) are easily crushed by external pressure due to structural instability, needing means for support. Simple flexible balloons blown-up with air at the same outside temperature don’t float because they are not displacing the air, just adding weight to puff them out against the external pressure. However, when hot air is used instead, which has lower density (so weight) they can be made to float. The trick therefore is to use an LTA gas for inflation with internal vessel pressure to counter balance the external pressure and create tension in the vessel membrane that stabilises it.

The LTA gas thus is not a lifting substance, instead being a structural way to stabilise the displacement vessel and get aerostatic lift from the external atmosphere to float. That’s how submarines and ships also float, except that it’s water buoying them!

Are they piloted?

LBA’s dirigible buoyant aircraft will be operable in various ways: 1) by a single pilot, 2) remotely controlled and 3) autonomously. Modern avionics and navigation instruments will be used and control is similar to helicopter operations because they fly in similar ways. The flight deck is the compartment below the main module. This position gives the pilot a 360 degree view of the surrounding airspace and ground operations. As well as many monitoring sensors around the aircraft, the pilot also will be able to view in all directions via CCTV cameras (something not especially available to pilots of other aircraft).

How do OD airships fly?

LBA’s OD airships will fly in a similar way to helicopters, except that they won’t tilt so much. They will remain essentially upright from pendulum stability when moving forwards, backwards, sideways, up, down or rotating around their vertical axis (precession). Due to the aerostat’s lenticular profile (like a discus) they have no apparent front, side or back. These aircraft therefore will be able to move in any direction without turning to face the flight direction.

OD capability has great benefits because it makes geo-stationary positioning (to pickup/deliver payloads) much easier. It also is great for geo-stationary platform applications at any altitude. Thrust vectoring from multiple cycloidal propellers ensures changes to wind direction are easily countered without any need to turn and with much less chance of being blown off station. They will be good for various patrol duties, able to float in silence (drifting with the wind as balloons do, when desired) only using power for course corrections or to fly against the wind direction.

Changes to compass heading, acceleration and slowing all will happen gradually and gently, so there will be virtually no g-forces felt – similar to free balloon flight.

Should I have concerns about 150 tonnes flying over my house?

Yes, always, but not especially from buoyant aircraft, where the LS-L150 was designed to meet heavy-lift needs for such capability. Safety is paramount.

LBA will comply with normal aircraft practices for safety factors and fail-safe methods, and our buoyant aircraft will be certified to similar standards as all other aircraft (including jetliners which, incidentally, weigh hundreds of tonnes and are accepted to fly over people’s homes). Our airships won’t behave as nonbuoyant aircraft do when their engines stop or systems and parts fail, falling from the sky – then crashing and burning. When our OD airship’s engines stop, intended as a routine aspect of flight, they will simply float on with the wind, as balloons do.

They also don’t have so many parts (like wings and tail surfaces) that could break loose. If the aerostat gets a hole in it, the main chamber isn’t pressurised, so won’t mind – perhaps eventually (if a big hole) quietly descending to the ground with descent rate controlled by the release of ballast and vectored thrust. Besides, operators of these aircraft mainly would be over-flying uninhabited regions to fulfil the duties needed.

How do your airships go up and down?

Ballast will be varied to trim them prior to launch (as for other airships) so that they will weigh just a little more than the buoyancy experienced, causing a small reaction against the ground – but essentially floating (so near fully airborne) due to buoyancy. The propellers then will be used for thrust to either hold their position against winds or move them in directions desired, including ascending and descending. The parachute effect of their aerostat will limit descent rate, even when overall weight is substantially greater than buoyancy. Our airships therefore will descend safely and gently without power due to the small excess weight.

How do the Cycloidal propellers work and what are their benefits?

See: Voith Schneider Propeller for a simple animation.

Cycloidal propellers look like paddle-wheels, since they have several straight blades equi-positioned around the edge of a rotating cylindrical framework. As they turn the blades pitch in a synchronised way under collective control (similar to helicopters). This enables the resulting thrust to be quickly vectored in any radial direction under full power.

The main benefit is rapid response vectored thrust for precision control in any 360 degree radial direction. Due to the way they operate and their installed position there also is reduced danger from failures, since the trajectory of freed parts is not towards the aircraft and breakaway energy is low compared with screw propellers and turbines. This makes for compatibility with the aerostat and personnel safety needs.

What is used for fuel and power?

We have sought to obviate carbon emissions and minimise the fuel burn rate. Our airships will use H2 as fuel and solar collectors to generate electricity, used to power the cycloidal propeller electric motors and aircraft systems. The aerostat design is ideal for solar panels because its upper surface is large, uniform and faces the sun at any one time (more so than cigar-shaped aerostats, hampered by the need to face the wind and their slender longitudinal form). The H2 fuelled engines and their drive-train plus water recovery systems will all be placed in an engine room in the underslung pod, which also houses the pilot’s control station. This ensures easy access, maintenance (even in flight) and much reduced outside noise. Exhaust emissions will be very low compared with airliners, mainly steam (which is an LTA gas that also is useful).

How will your airships land?

Being buoyant aircraft, our airships won’t truly or generally land, remaining airborne throughout their life (buoyed up by the atmosphere). They instead will be captured and then held, restrained by mooring lines next to the ground in a similar way to ships next to their births. OD airships thus will be fixed against movement by mooring lines – not so easy for UD types, which need to weathervane around a mast to minimise aerodynamic loads. Otherwise, similar to helicopters, our airships will be able to stop in the air over a mooring or pic&put site (controlled with thrust) and then descend vertically. No runway required!

During payload pickup and delivery, an objective is that our airships should not be restrained; instead holding station (as helicopters do) in a pseudo-hover situation under autonomous control above the ground. The legs one sees under the pod are ‘fenders’ to cushion and protect the lower structures when bumping against the ground (so not landing gear).

Landing is possible by rapidly venting the LTA gas in the aerostat. This is a way for emergency use to prevent unintended breakaway from the mooring restraints or to prevent rapid ascent after a heavy payload is dropped or when strong updrafts are experienced to become HTA. If deliberate landing is necessary for other purposes (e.g., for maintenance or repair) then, while moored, the under-slung parts will first be removed. The aerostat then will be hauled down to ground level and deflated using upper vent valves, when it will collapse against the ground (so no longer airborne).

How will your OD airships be moored?

Our OD airships will be moored in a fixed way with multiple lines at equi-spaced positions around their circular aerostat’s perimeter to anchor points on the ground. The fixed arrangements ease maintenance compared with UD airships swinging at a mast. For storm resistance the aerostat also will be drawn down close to the ground and protected with a surrounding skirt (cloak). The fixed state (no weather-vane movement) means the mooring loads will be more evenly spread across multiple anchors and the mooring site may be considerably reduced in size compared with HTA aircraft airfields and typical UD airships at their moorings.

What is the aircraft made of?

Our aerostats will be made from strong non-rigid laminated fabrics stabilised with mainly LTA gas and some air. The chambers inside will be made from similar materials but of lighter weight. The structures below may be metallic (typical aluminium airframe) and/or use composite mouldings. Their suspension lines are similar to ships’ mooring lines (strong synthetic fibre ropes). A central umbilical trunk, which looks like a rod (but is not primary structure), may be used as a service trunk for personnel, air and systems between the lower structures and the aerostat, so would be made from light laminated fabric.

How will your airships be built?

Our airships don’t necessarily need a hangar for inflation, assembly or maintenance, where they were designed together with mooring and protection arrangements to obviate the need for sheds to house them. However, hangars are convenient if available to enable build and maintenance activities in a more comfortable environment. Such hangars may be large air-stabilised or light structure fabric covered buildings, for which we have a number of designs prepared. These temporary buildings are ideal as they are low-cost and mobile. And, whereas airship designs of the past have required large hangars for maintenance work, OD airship aerostats act as their own shelter when moored and fitted with a ground skirt for protection, an extra to consider.

That said, the basic parts: aerostat, nacelles, propellers, ground facilities, etc, will be built to order by specialist approved organisations who will deliver them to us for assembly, test and airship certification. We thus will be the technical design authority for buoyant aircraft produced (needing DOA approval by the airworthiness authority for the purpose). We don’t have plans at the moment to undertake parts production ourselves, so will be reliant on established organisations for them. This enables us to be an SME in a similar way to past companies like Airship Industries Ltd. We have a Strategy for stepped development starting with small airships that are readily doable.

When checked out and approved, we then will package/box and supply them to operators who are trained and approved for the purpose. We also will provide the necessary documents, procedures, training, licensing and support necessary for operators to set up and go from.

Where will your airships be built?

We are based in the UK, where our initial prototype build, test and type certification arrangements have been set up. However, we also have partners in Germany, the USA, Canada, Africa, Malaysia and Australia, where further arrangements are in hand. We plan to expand globally when possible, which depends on enough interest from people who want the capability that LBA provides. This needs orders or agreements for them. As our various aerostat and airship designs gain type certificates we will enable further build arrangements to suit international demand. Interested parties should register with us as a first step for collaboration.

Will I be able to hire an LS-L150?

When LBA fulfils our development objectives then yes, eventually – so not at the moment or until we’re able to develop this rather big aircraft. It’s not supported by outside investors at the moment!

However, we know it’s possible and are confident about the design being able for the purpose, so would appreciate registered interest, helping us to show there’s a serious market to serve and that it’s wanted.

Compared with other offerings for such capability, we think our proposal is the only one that can survive or could become successful, both at a price operators would succeed with and from the way the aircraft is designed for the circumstances of operation under real weather conditions with the state of the industry as it exists today; not as ideally portrayed by others. We are realists about the objective and won’t be pursuing its development until the spadework necessary to enable it is done.

We will work to certify it for flight in all parts of the world. However, we’re not planning to be an operator providing the services that it may fulfil, which needs other organisations to step up to the mark for that. Nonetheless, we will develop operating capability – necessary for the certification process and to train the people who become operators. They’re the people to ask about hire and who should register with us to discuss the possibilities of becoming an approved operator.

For qualified organisations, we also will offer manufacturing license options.

In the meantime, we intend to follow our strategy for development, which starts with readily doable projects focussed on getting income to do more. A prime objective at the moment is to complete the development of the LS-L6 series, LS-L15T, Patroller 3 & LS-L25 and provide them to operators who then may get on with setting up the network of bases to ultimately enable LS-L150 operations.